How to find ideas for your research*

Finding a dissertation topic

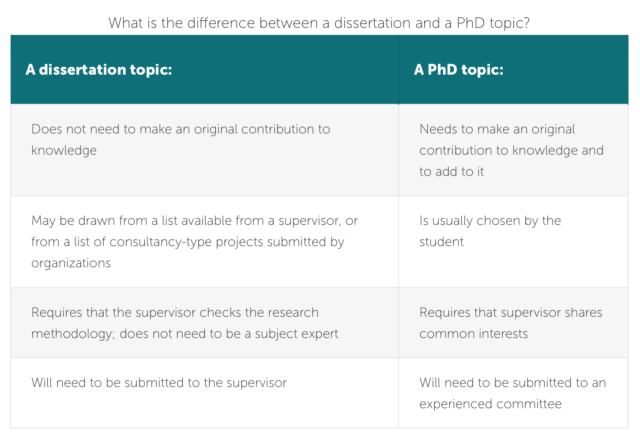

Here we are talking about a dissertation project done in satisfaction of the requirements of a masters’ degree, such as an MBA. The idea behind this sort of dissertation is to gain basic research skills: unlike a PhD, there is no requirement for the research to be original or extend knowledge.

It is usual at a post-experience level to link the project closely with future career aims, and hence the project topic needs to be one of practitioner relevance, assuming the ultimate career destination is in this field. It is also common, given that many students will have had a few years in the workplace, or if part-time still be working, to draw the topic from some situation in the work-place, for example provide a solution to some problem, develop a new system, or review a campaign or some innovative way of working. Some schools encourage students to do consultancy-based projects, providing lists of opportunities.

There are various other ways of sourcing topics:

- Using techniques such as relevance trees and morphological analysis – see next section.

- Looking at previous projects, which will probably mention areas for further research.

- Brainstorm with other students.

- Look at abstracts in online databases, and list ideas you find interesting.

![]() Be aware of the following:

Be aware of the following:

- Your project must conform to the required academic standards, which will usually mean including a research methodology. Consult your tutor and your course handbook.

- You have the requisite technical background, e.g. in statistics or mathematics, or will be acquiring these skills as part of the course.

- The project should not be too difficult for your level: beware of topics which do not have much information on them in your otherwise well-stocked library, or where the language is overly technical.

- There must be sufficient data – this is particularly relevant if you are doing a company-based project, make sure that your sample is large enough.

- Will your supervisor have sufficient expertise to help you, and will there be other technical expertise, e.g. computing facilities to help you with the data.

- Will the library hold sufficient secondary data, or if not will you have access to a good library that does?

You will probably need to do a research proposal which will need you to outline the topic very clearly, and will also need to state your objectives and your research methodology, as well as the intended outcome.

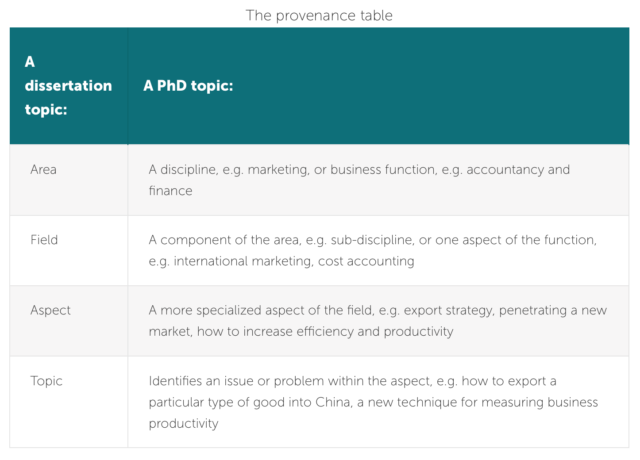

Using the provenance table

Given that management is an interdisciplinary topic, you need to understand fairly early on how your topic fits into the whole body of knowledge. A.D. Jankowicz, author of Business Research Projects advocates using a technique known as the Provenance table and works as follows:

Finding a PhD topic

Inability to identify a suitable topic is a very common problem with PhD students, while a topic that isn’t quite right – due to lack of clarity, insufficient novelty etc. – is a common cause of PhD blues further down the line.

In this section

While many people stumble on a PhD topic by chance, it is better to adopt a systematic approach, such as that advocated by Sharp, Peters and Howard (2002). You can read more about it in The Management of a Student Research Project, by John A. Sharp, John Peters and Keith Howard, Gower, 3rd Edition 2002, pages 26-47.

Identifying the area of study

This is self evidently the first step, and should not be too difficult; in all likelihood, it will be determined by some interest generated by previous study or by employment. This in itself will suggest a supervisor, although for some the desire to work with a particular individual or research centre comes before the particular interest.

Finding the supervisor

This is a very important relationship, and it is important that you make a careful selection. Indeed, for some the desire to work with particular people comes before the choice of subject.

This is a very important relationship, and it is important that you make a careful selection. Indeed, for some people the desire to work with particular people comes before the choice of subject.

Abby Day, author of How to Get Research Published in Journals, is currently doing a PhD in the sociology of religion. Having spent many years as a consultant in the field of management and business, she became frustrated because she wanted to gain a greater exposure to the theoretical underpinnings of management, in sociology. At the same time, a change in her health made her look for a career change into research, which she could do more at her own pace. This meant doing a PhD which would give her the necessary training in research skills. She decided that she wanted to study organizations, and she became interested in the “Spirituality and the workplace” movement. She also wanted to look at contemporary belief systems, which she saw as playing a large part in how organizations work, and came on her topic after discussion with her supervisor and reading around the subject. Indeed, the choice of subject was partly dictated by her desire to work with people in the Department of Religious Studies at Lancaster University, UK,which was situated within the Social Science, and not the Arts Faculty.

Here are some things to bear in mind:

- Is he/she eminent in the chosen area?

- Have they recently published articles, managed funded research projects, spoken at conferences?

- What is their record in terms of student completion?

- Do they also have the skills in terms of research methodology?

- How accessible are they likely to be – will they be able to meet with you on a regular basis and be there if you run into difficulties?

- What are their views on the management of student research – will they provide plenty of help in initial stages, and then stand back as the research progresses?

- Will you be able to form a relationship of trust with them – will they look out for you personally and professionally, speak well of you, defend your work, help you graduate in a reasonable time frame, and always give you credit for your work?

- Will you be able to establish a rapport with them not only in the above respect, but also in terms of supervision style?

- Will they provide a pattern of supervision which will suit your needs – will you be looking for someone who can give constant advice and feedback, or someone who will be prepared at times to stand back and let you think and reflect?

- Will they provide you with other opportunities for research apprenticeship, for example helping them write articles to which your name will also be added?

- Are they well connected in the field, so that they can help you gain employment at the end of your thesis?

![]() It is important to consider not just your supervisor’s interest in your area, but also whether if he/she leaves, the university has sufficient personnel to support you. For that reason, it can sometimes be a good idea to choose somewhere which has a research centre in your given topic.

It is important to consider not just your supervisor’s interest in your area, but also whether if he/she leaves, the university has sufficient personnel to support you. For that reason, it can sometimes be a good idea to choose somewhere which has a research centre in your given topic.

Initial selection of topic

You are now at a point when you have to narrow your focus to a specific topic, or topics (it’s probably best to have several topics to start off with, from which you can select). At this point, you change your role: whereas previously you have been an explorer, looking for gaps in knowledge on which to base your research, you become a detective, looking for solutions to problems. (Read Pat Cryer, The Research Student’s Guide to Success, pp.59-61 on, the different roles of the researcher: explorer, detective, visionary, and barrister – and see a diagrammatic version below).

Make sure of the following:

- Your supervisor is interested in your topic – they will spend a lot of time on it too. You can also ask them to come up with some ideas.

- Your topic interests you – this is essential as you will be spending a long time on it, so you need to keep up your motivation! You need to own and shape your idea – you are making a big emotional investment.

- You are doing something of interest to the research community.

- You are addressing a real problem as opposed just to plugging a gap in knowledge – you should be saying, not “I want to do research on branding” but “I want an answer to a specific question”, such as “Why do companies seek co-branding?”

- You have picked something truly original – this is the defining criteria of PhD research. You must be able to convince both yourself and others of the novelty of your topic.

- You can complete in the necessary time frame.

What is originality? Estelle M. Phillips and Derek S. Pugh, in their book How to get a PhD(3rd Edition 2000, Open University Press) list the following ways of being original:

- Setting down a major piece of new information in writing for the first time.

- Continuing a previously original piece of work.

- Carrying out original work designed by the supervisor.

- Providing a single original technique, observation, or result in an otherwise unoriginal but competent piece of research.

- Having many original ideas, methods and interpretations all performed by others under the direction of the postgraduate.

- Showing originality in testing somebody else’s idea.

- Carrying out empirical work that hasn’t been done before.

- Making a synthesis that hasn’t been made before.

- Using already known material but with a new interpretation.

- Trying out something in your country that has previously only been done in other countries.

- Taking a particularly technique and applying it to a new area.

- Bringing new evidence to bear on an old issue.

- Being cross-disciplinary and using different methodologies.

- Looking at areas that people in the discipline haven’t looked at before.

- Adding to knowledge in a way that hasn’t been done before.

The literature review is a very important in the initial selection of the topic. This will be more a matter of doing extensive reading rather than a formal literature review, which will happen at an early stage of the research. Because a PhD is an addition to the body of knowledge, you need to have a good idea of what the body of knowledge is in that area. Your supervisor will be able to direct you to the most useful starting points as you do your survey of the literature, but here are some suggestions:

- Reports of research in peer-reviewed journals, looking in particular at their suggestions for further research.

The article Equity in corporate co-branding by Judy Motion, Shirley Leitch, and Roderick J. Brodie (European Journal of Marketing, Volume 37 Number 7/8) ends as follows:

“The role of marketing communications in corporate co-brands and the equity courses that emerge offer a potential agenda for research and further theory development about the nature of co-branded equity. Such research will further understanding [sic] of how co-branding offers corporate brands the opportunity to move beyond sponsorship relationships to partnerships that redefine the brand identity, discursively reposition the brand and build co-brand equity.”

- Theses and dissertations, conference proceedings and general reports, which may have similar indicators of future research.

- Reviews of the field of study (sometimes, literature reviews are published in academic journals).

- Books and book reviews (the latter provide useful indicators of the former’s contribution to knowledge, and can often be accessed via citation indexes).

- Conference announcements, reports and proceedings – look at tracks and themes.

- Reports in the media – are there particular issues that keep coming up, particularly ones that will be important to managers?

Professor Devi Jankowicz says that research students often come to him with a general idea for a PhD, for example, change management in China. They may well be reacting to something that interested them in their masters or undergraduate course, or to something in a textbook. The task is to then be a lot more specific. He urges them to go away and write two to three sides of paper on what they want to research and why, what has been done so far and what would they do to move that area of knowledge on. He is not expecting a polished answer, and it is clearly impossible to do a proper literature review in the space, but it serves as a trigger to get people reading scholarly articles as opposed to textbooks and to thinking what their contribution to knowledge will be. Much of the first year will be spent doing a literature review and refining the research proposal.

In addition, ideas may come from the following:

- Issues arising during previous study.

- Conversations with practitioners, colleagues, potential users of the research.

- A personal interest.

- A work interest – especially if you are doing the PhD part-time, it is very important to pick a topic that complements your work.

Sudesh Sangray submitted (November 2004) his PhD on market efficiency. He first became interested in this topic when he studied it at undergraduate level. He decided to look at the impact of company announcements on stock market share prices, but had difficulty deciding on a sample. His supervisor suggested that he focus on a new stock market that had just been born in London – the Alternative Investment Market

The following techniques can also be used to generate topics:

Analogy

This can work in a number of ways: Sharp et al. (op. cit. p.35) give the example of looking at small business within the framework of intermediate technology; you could also have an interest in a particular topic, and read about a research methodology or a conceptual framework in another field and decide to apply the latter to your own topic.

Relevance trees

Here, you start from a broad topic and draw ‘branches’ from it until you have narrowed down to a particular area of interest.

Morphological analysis

Here, you need to define the key factors/dimensions of a topic (which could also be your field of interest), then list the factor’s key attributes (with examples) and finally, combine them in different ways. (See Sharp et al. pages 36-38.)

Doing a reality check

Once you think you have a good topic it’s important to consider the following before going ahead (see the diagram above):

Is it feasible?

This is really about whether it’s possible to conduct the research and get a result, or whether there will be insurmountable obstacles. You should consider:

- Will there be sufficient data and will you be able to gain access to it?

- If you want to set up a field experiment, conduct a survey, interview key people, or observe the workforce, will this be possible, in other words will you gain cooperation for your research design with your subject?

- Will you be able to complete the topic in the time available? Draw up a research plan, with a schedule and objectives, and see if you can meet your deadline.

- Do you have, or will you be able to acquire or gain assistance with, the necessary technical skills? For example, many methods require use of statistical analysis techniques: will you be able to acquire these, is your supervisor/other tutors to whom you will have access able to help you? Will there be help with any necessary programming and will the requisite software be available?

- Will you be sufficiently well covered financially for costs over and above tuition and living expenses, for example, for the cost of carrying out a survey, travelling to visit companies etc?

- What are the risks that the project will be impossible to complete?

Is it valuable?

What will be the value to the community at large? Will companies be able to find better and quicker ways of doing business? Will it make a difference to the lives of managers? Will you be able to demonstrate a new educational method? More data on health care in a particular part of the world? These days it is hard to obtain funding if you cannot demonstrate the social or wealth creation aspect of your research.

Is it symmetrical?

Issues of symmetry concern the uncertainty of results of a particular piece of research, and whether the possible outcomes of the research, and the answers to the questions which it poses, are of equal interest. If there is no positive outcome, will the research still be valid?

If you were to conduct a study on the incidence of smoking and heart disease, were you to establish that over a sufficiently large group there was no link, then you would excite great interest; if on the other (probable) hand you were to establish a link, then this research would be of doubtful value.

The UK government is currently thinking of banning ads for junk food until after 9pm in an attempt to combat childhood obesity. Studies of other countries where this had been done, whether or not they established a link with purchasing patterns and subsequent obesity, would be highly relevant to this debate.

Is there sufficient scope?

This is related to what beliefs are held in the area, and how strongly they are held. For example, linking smoking and heart disease (as in the example above) is of value but little surprise.

The roles of a researcher

We have talked here a lot about the stages in the identification of the topic. It may also be useful to consider the researcher as pursuing different roles.

Post PhD: developing a research stream

We are grateful to Professor Robert Morgan of the University of Cardiff for permission to reproduce copyright material in this section.

To the student, the completion of a PhD can seem like the end in itself – that is the career end as opposed to that of the PhD!

In this section

At every stage in one’s career however, it is important to have one eye on the next move in the game plan, and the PhD is no exception.

It is important to consider not only “passing” the viva and getting the all-important first job, but also increasing one’s potential as a researcher through the acquisition of skills, and the development of a publishing plan. Both the former and the latter are very important if one is to remain in academia. In any event, having produced a standard of research sufficiently high to earn you a PhD, it is likely that with a little revision you will have some form of publication.

Graham and Stablein quote the following list of anxieties amongst research students (links to other parts of the site are given to useful resources):

- How can one envision the publishable outcomes of a research effort in advance? (See Should I publish before completing my PhD?)

- How does one “carve up” a thesis or other large project into separate pieces? How much is enough for a given article? (See Should I publish before completing my PhD?)

- How does one choose what not to include in a paper? How detailed should a procedure/method section be? How speculative should a discussion section get? How much ex post facto logic is ethical/acceptable?

- What is the appropriate journal for the article? (See How to find the right journal.)

- Are there barriers to publishing on topics not already in the literature? Is there a bias against radical perspectives and topics?

- Can one publish non-quantifiable empirical work? (See How to conduct empirical research.)

- Just how “original” and new must an idea be to be publishable?

- Do publishable articles have to be written in a “boring” style, or does it just happen that way?

- Does one have to “go along” to get published?

- How important is networking, going to conferences, workshops, colloquia and becoming known by the “right” people to getting published?

- Is co-authorship a liability? (See How to collaborate effectively.)

- How “blind” is blind review? (See How to survive peer review and revise your paper.)

Source: Graham, Jill W. and Ralph E. Stablein (1985), “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to Publication: Newcomers’ Perspectives on Publishing in the Organizational Sciences”, in L. L. Cummings and P. J. Frost (Eds.) Publishing in Organizational Sciences, R. D. Irwin, Homewood, IL., pp.139-140.

How research differs post-PhD

When you work on a PhD, you will be working on one large project. However, on finishing this project, it is advisable to work on a number of smaller projects. This will be a good way of spreading the risk and avoiding putting all your eggs into one basket by working on one project in the hopes of being published in a top quality journal.

Working on a number of projects will require juggling – projects may be at different stages, one at the literature review stage, one at the design stage, one at data collection etc.

Another difference is that whereas a PhD is a solitary pursuit, when you are in the mainstream of academia collaboration is more usual. This provides a good way of cross-fertilizing ideas and sharing the burden both of researching and article writing.

In looking for collaborators, it’s very important to find people you: a) get on with, b) trust to involve and consult with you at every stage, and c) have a similar theoretical perspective to you, or, if they have a different theoretical perspective, your combined perspectives will compliment one another rather than fight.

Should I publish before completing my PhD?

It will obviously give you a good head start in publishing if you can publish part of your thesis in a scholarly journal. Your main constraint will be the length of a typical journal article, which is around 6000 words. It is therefore neither advisable nor usual to distil your whole PhD, but rather to take a small section of the data which relates to a particular theme and analyse that. For example, if you used interviews, you could take a selection of these, or if a questionnaire, some questions which related to a particular theme. In writing the literature review for the article, you would obviously need to summarize what you had read and focus on those sources relevant to your chosen theme, while the similar considerations will apply to the research methodology section.

Although for purposes of research credibility you will probably want to focus on scholarly journals, there is no need to confine yourself to these. You might also consider, as a way of reaching your equivalent professional community and showing the practical implications of your work, publishing in a practitioner journal. See How to write for a practitioner journal.

Dr Andrew Pressey (working in a UK university under the looming Research Assessment Exercise) maintains that now there are a great many pressures on research students to publish articles before they have submitted their PhD. He therefore advocates consideration of publishability while selecting a topic, and also of the fact that if the student goes into academia, he/she may continue to research around the topic for some time. Is your topic of importance to other researchers (as indicated by the literature, and also by its appearance in conference tracks)? Will it continue to be important in a few years time, or will it date, is it merely a fad?

Ways of developing a research trajectory

The important thing is to see the big picture when you are considering your research: think what field you want to be in, what areas you want to develop, and plan for continuity.

“Identifying and following a particular research trajectory is to be recommended. Expertise has limited scope and continuity in research is almost always rewarded. The biggest challenge is to manage the development of the research, and the associated projects, in an appropriate way. The best way is to seek advice and mentoring – in the informal rather than the formal sense of seeking out knowledgeable people and key scholars in the field. Networking at conferences and workshops is just as valuable; the “meet the editors” sessions at conferences can be useful and often they explain important but subtle issues to do with their decision-making; something you never see in the Notes for Contributors. It is also important that authors make sure they hear about all the calls for papers.”

Professors Rob Morgan and Jeryl Whitelock

Editors of International Marketing Review

Quoted from an Emerald meet the editors interview.

Here are some ways in which you can find suitable research streams:

- Read professional journals and spot interesting conceptual developments, as well as questions which:

-

- Have not yet been addressed.

- Have been partly or unsatisfactorily resolved but could be further investigated.

- Are raised in the “further research” sections at the end of articles.

- Look at the Research Priorities of your relevant academic institute, such as the Marketing Science Institute, the American Academy of Marketing, the American Academy of Management, the British Academy of Management, etc.

- Attend the main conferences in your area – both leading and specialist. Look out for the issues being debated, comments from presenters and other attendants at seminars.

- Discuss with colleagues.

- Keep an eye open for what is going on in relevant practitioner fields – for example, are there particular issues being debated in the business and professional media, which could do with some theoretical basis and empirical research?

- Develop a dialogue with other researchers and seek to join a network or email discussion group.

- Read widely outside your discipline in cognate areas and import research methodology, theoretical perspectives etc.

- Be informed about Calls for papers: look out for Calls in journals, subscribe to ELMAR etc.

- Don’t spend too much time just looking for the “hot topics”!

Here is what some leading journal editors have to say about hot topics:

“Rather than endlessly searching for today’s “hot topic”, potential contributors to the Journal of Marketing are well-advised to write and do research in those areas where they believe they can make the most contribution.”

Shelby Hunt

Journal of Marketing, Fall 1985.

“Over the past three years, I have been asked literally dozens of times (usually, but not exclusively by Ph.D students) what the hot topics in consumer research are… To attempt to answer that question, officially and for the final time, I suggest that you look within yourself. A topic isn’t hot for you unless you decide it is. It is safe to say that the very best researchers in our field follow their own instincts in selecting research topics… Their instincts are grounded in an expertise emanating from a total immersion in the topic area: reading the relevant academic literature, scanning the trade press, talking with industry researchers and colleagues at conferences, trading working papers and ideas on a network of scholars with similar interests, and so on. It is a commitment to a program of research that makes it work. You need to become an absolute expert on your subject.”

Richard Lutz

Journal of Consumer Research, 1990.

Here are some tips:

- Find a reasonably broad focus that includes several interesting problems: it is important to have a strong theory base, but equally important to focus on particular problems as that will give you a novel contribution.

- Have a theoretical anchor but have multiple levels of analysis – e.g., if you were looking at organizational learning you could do so both across different organizations and within them (i.e. looking at different functions). Push off into new areas – the critics will be more receptive and a bit less critical than if you were to focus on low-risk, safe, and well-known areas.

- Make connections: link your area of research to other problems in your area, and to existing frameworks and methods.

- Seek funding! (See How to make a grant application.) Not only will this provide you with a budget for your research, but it will also legitimize your area and your role within it.

- Beware of getting too fragmented in your research: in your early years as a researcher, 2-3 projects at a time are adequate; later, maybe more.

- Be aware of the opportunity costs of pursuing research topics: be prepared to drop a topic that doesn’t appear to be leading anywhere.

- Be opportunistic: be on the lookout for new ideas, especially towards the end of a project.

- Take charge of your learning: learn as you go, try and make sure that you create a helping environment for yourself, with plenty of people you can turn to for help and mentoring.

Be confident in your views! There will always be a diverse number of research topics that individual researchers find hot, i.e. ones they see as:

- Intellectually challenging

- Interesting

- Intriguing

- Invigorating

Making a contribution to knowledge

The best way of getting an article accepted is to make an incremental contribution to knowledge, one which will cause:

- A manager to manage differently.

- A researcher to research differently.

- A lecturer to teach differently.

An incremental contribution to knowledge is one where: solutions or enhancements are proposed to overcome the difficulties.

An incremental contribution to knowledge is not one where: the researcher merely enumerates the deficiencies in previous works.

Some ways of making a contribution to knowledge:

- Challenge conventional wisdom and prevailing beliefs. For example, the presumed causal direction of the relationship between variables.

- Refute or critique a theory currently in vogue, or propose an alternative explanation or perspective.

- Test a theory that has been developed but not tested.

- Provide better measures or better data.

- Replicate a particular design in another context.

- Provide additional theoretical or empirical insights.

- Present corroborating/non-corroborating evidence.

- Look at common practices which do not yet have a good theoretical base, and conduct some empirical research and develop a theory.

*This article was published in https://www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/archived/research/guides/management/research_ideas.htm